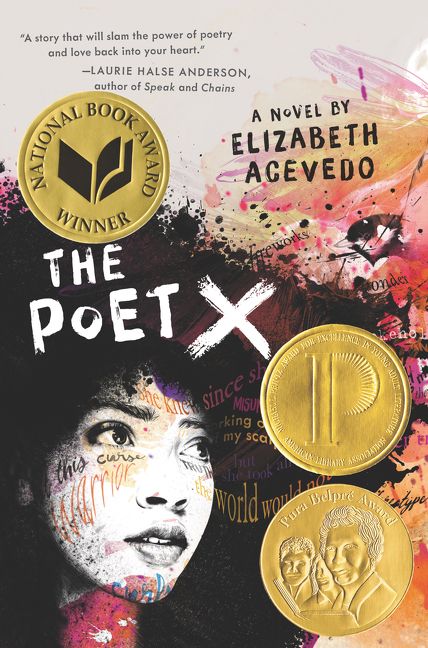

A few days ago I was doing a literary translation workshop with French teenagers in London, using as my English text a slice of Elizabeth Acevedo’s splendid, National-Book-Award-Winning The Poet X, which I’ve had the pleasure (/honour/ insane luck) of translating into French.

Elizabeth Acevedo, in case you haven’t heard of her, is this remarkable spoken word poet and writer:

The Poet X is the Künstlerroman of a young Dominican-American woman who discovers spoken word poetry, rebels (selectively) against her family, loves her brother, and loves, too, a sensitive young man in her Biology class. She writes in a notebook, and she writes things about her everyday life, such as church, food, masturbation, and street harassment:

(Transcr:

It happens when I’m at bodegas.

It happens when I’m at school.

It happens when I’m on the train.

It happens when I’m standing on the platform.

It happens when I’m sitting on the stoop.

It happens when I’m turning the corner.

It happens when I forget to be on guard.

It happens all the time.)

This is the poem I asked the French teenagers to translate (well, only the first stanza – we only had an hour). As you can guess, there’s plenty of fascinating challenges for a translator there, and we always begin by reading the poem out loud, testing out different stresses, different rhythms, feeling the beats and letting the sounds fill our mouths, before we start making decisions about translation. I won’t focus on all the aspects in this blog post, but I want to talk about one particularly interesting thing that came out of the exercise.

The first stanza, obviously, makes striking use of the anaphora ‘It happens’. What is ‘it’ that happens? It’s alluded to in the next stanza – touching, allusions, compliments. The usual catcalling and groping sort of business.

How do you translate that into French? Well, there’s at least one absolutely literal translation: ‘Ca arrive’ (it happens). The problem is the hiatus (a hiatus is what happens when you have to force a break between two similar-sounding vowels): Ca-arrive. That a-a sounds fairly unpleasant to the ear – this is what I think secretly, but of course I say nothing to the teenagers ; it’s my opinion. But among the six groups that day, no one opted for ‘Ca arrive’.

Two groups opted for the next most literal option, ‘Ca m’arrive’ (It happens to me), which has the advantage of getting rid of the hiatus. Interestingly, this option makes the victim explicitly central in the French text – no way of avoiding this ‘m’ which explodes from the front of the mouth and provides a nice labial echo to the ‘haPpens’ in the English version. Full disclosure, this is the one I picked for my own translation, too.

Another table chose, interestingly, not to translate ‘It happens’ at all. Instead, they started every single line directly with ‘Quand’ (when). The effect was funny: the stanza becomes a bit of a riddle, to be solved in the very last line. ‘When I’m there, when I’m there, when I’m there, when I’m there… It happens’. More suspense, but less emphasis on the relentlessness of the harassment.

Another table chose, interestingly, not to translate ‘It happens’ at all. Instead, they started every single line directly with ‘Quand’ (when). The effect was funny: the stanza becomes a bit of a riddle, to be solved in the very last line. ‘When I’m there, when I’m there, when I’m there, when I’m there… It happens’. More suspense, but less emphasis on the relentlessness of the harassment.

Another group opted for the hugely alliterative ‘Ca se passe’ (pronounced ‘Sasspass’), which more or less means ‘It happens’. I like this solution, which sounds like hissing, and preserves the plosive ‘P’ of ‘haPPens’. It is perhaps the closest to the source text in both meaning and effect. I had considered it (and am still considering it) for my translation.

Another group, finally, had an idea I hadn’t considered at all, and which I find especially interesting. It is to begin each line with ‘Ils le font’, namely, ‘They do it’ (with the ‘ils’ explicitly male in French). Complete change of focus all of a sudden: the perpetrators are at the very beginning of the line, of each line. The impersonal ‘it happens’, which makes it sound like it’s some kind of unavoidable meteorological phenomenon, suddenly acquires a body (even several bodies: a threatening army of bodies); it acquires malevolent agency, and it acquires a gender.

A radical solution, which arguably lacks elegance in its sounds, but strongly signals the translator’s commitment to naming and blaming the perpetrators. Before you ask, the table who came up with this solution was composed exclusively of boys.

What a world of connotations separates ‘Ca m’arrive’, which focuses Acevedo’s text onto the victim, ‘Ca se passe’, which renders the impersonal inevitability of the original, and ‘Ils le font’, which foregrounds the harassers.

All three solutions are acceptable, and all commit the translator differently. Those little decisional acts we perform on a text we translate are what makes a translation a literary practice, and a practice through which words have an effect on the world. Each of those three poems would have a different effect on the world, because they each focalise our attention differently.

Three ways of looking at street harassment. And I was of three minds.