Last week I wrote a blog post deploring the fact that I couldn’t write slowly. In response, two of my friends suggested I blogged about how to be ‘productive’. I’m a bit ambivalent, since, as hinted in that blog post, ‘productivity’ has a dark side. It can be efficiently generated by the cultivation of guilt, worry about the future and insecurity in children from a young age (I’m looking at you, French educational system), as well as by inordinately high standards.

So my immediate sarcastic response was: Tip number one: set yourself irrationally high goals, self-flagellate every time you don’t work enough to attain them, find people who are much better than you and mull over how superior they are, and for good measure, add the threat of never finding a job. Your productivity will rocket, I promise.

Well, let that be a disclaimer: even though this is a ‘tips’ blog post, there are issues with ‘tips’ about productivity, just like there are issues with ‘tips’ about losing weight, for instance.

But here are a few things that I do find genuinely useful in increasing productivity, that is to say, in my case, getting (preferably good) words on the page, whether academic or fictional, and making sure they get published (i.e. editing, revising, referencing, etc); and doing teaching-related work.

- Switching off the Internet entirely

Just as I’m writing this, a little (1) pops up on my Facebook tab. I have to check what it is, because it could be someone tagging a picture of me drunkly lap-dancing in a bar. Let’s see. No, it’s fine, it’s just someone I friended in 2008 mass-inviting all his Facebook acquaintances to sponsor his half-marathon on a space hopper. I’m never going to sponsor him, but I still read the whole description and end up wikipediaing the charity he’s space-hopping for, which knits socks and scarves for yellow-bellied marmots. I suddenly remember I have a blog post to write, but now a little (1) has appeared on the Outlook tab…

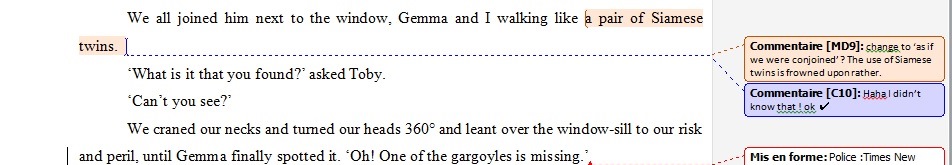

Sorry, what? Oh yes – the Internet. Let’s not write that blog post online – too distracting. Write it in a Word document instead. Internet can stay open behind Word. Oh no it can’t, because some idiot at Microsoft thought it would be an excellent idea to make Word vaguely translucent at the top, which means I can still distinguish the little (1)s through a half-hearted vapour of pixels.

Solution: turn it off altogether with Cold Turkey (SelfControl for Mac users). I couldn’t have written anything in the past two years without Cold Turkey. It didn’t even get a mention in my thesis acknowledgements, because I preferred to pretend that real humans such as my supervisor, friends and family were more responsible for its completion, which is a lie, however much I love them.

Those pieces of software only block the websites you want them to block, which means you can still use JStor and Project Muse, where procrastination opportunities are few (until you start typing up your own name to see what comes up and this does).

Those pieces of software only block the websites you want them to block, which means you can still use JStor and Project Muse, where procrastination opportunities are few (until you start typing up your own name to see what comes up and this does).

- Pomodoroing through multiple projects

I do this when I work on very many projects that are all at different stages of development, because that’s when I’m most at risk of using the exciting ones as excuses to procrastinate on the others. The Pomodoro technique basically states that you should set yourself short spans of time for work, interspersed with breaks. Strictly speaking, it’s supposed to be 20 minutes, but that’s too short to do anything constructive in academic or fiction writing.

I make myself work generally for an hour or an hour and a half on many projects everyday, strictly interrupting the one I’m doing when time’s up (yes, even in the middle of a sentence) to start work on the next one (or take a break).

Breaks can be used to check and reply to email, though it’s much better if you can actually force yourself not do anything at all.

I use the Pomodoro technique only when I’m feeling overwhelmed by the quantity and variety of different projects. It’s also much easier during student holidays, when there aren’t too many meetings, supervisions and essays to mark.

The good thing about this technique is that you never work long enough to get bored of the projects. If anything, it makes you frustrated when you have to stop – which means that the next day, you’re happy to find that piece of work again.

- Taking on more work, or setting earlier deadlines.

I find that productivity augments, rather than declines, when I’ve got more to do. This is, in part because although I can (on good days) focus intensely on writing or research for up to six or seven hours, it’s extremely rare when I can have that focus for one project. Paradoxically, taking on more projects and making sure you’ve always got one or two deadlines soonish makes me achieve more and feel happier.

- Keeping a strict and very subdivided to-do list.

I list everything, even things like ‘reply to X’s email’ if I know it will take me more than 3 minutes to compose. If I have 20 undergrad essays to mark, I’ll list the names of all 20 people and cross them out as I go along. Purely psychological, of course, but those manageable tasks give the impression of being productive, which leads to actually being productive.

I also have 4+ separate to-do lists corresponding to different domains (fiction, admin, research, teaching, etc.), which avoids clutter. My to-do lists are on (virtual) post-it notes on my desktop, like (virtually) everyone else I know.

- Doing either work or leisure activities

Wait but Why says it perfectly: there are two types of good weeks: days when you achieve something that ‘improves your future or that of others’ (even in small ways), and weeks of pleasure, leisure and enjoyment. Both at the same time makes for an ‘ideal’ week, which is rare.

And in-between, there’s a wearisome kind of activity, where you know you’re not actually having any fun, but you’re not doing anything particularly valuable either. This is the case, for instance, if you spend most of a day half-heartedly writing a few sentences, checking email, marking half an essay, checking the news, reading half a paper, checking the weather, etc. It’s tiring and makes you feel gross, while both real work and real leisure makes you invigorated and happy.

- Picking the right times for small projects or admin tasks

It’s tempting to get small tasks or long tasks that don’t take much brainpower out of the way (i.e. filling in forms, doing tax returns etc.). But then you just end up wasting valuable energy, and possibly spending too much time on them out of a semi-conscious desire to procrastinate work on important stuff. Again, I find it useful to time those important but boring activities strictly, and stick them at moments of the day when you know you won’t be very switched-on anyway.

- Using up as much available time as possible.

It’s hard to focus on anything when you know you’ve got to leave in 10 or 20 minutes, but with some tasks it’s entirely possible. I wrote most of this blog post in chunks of 5 or 10 minutes. I have a number of tasks on my to-do list that I know I can do in instalments, quickly dipping in and out when needed.

- Sacrifice some things.

For instance, this blog and my French one. I don’t care (much) if I don’t have the time to deliver the weekly Wednesday post.

I’d be curious to hear what you do to increase productivity, and/or take issue with such blog posts as this one on ideological grounds.