Summer’s coming, undergradate and MPhil dissertations are due soon, and it’s time to get articles sent to journals before the August and September lethargy gives peer-readers even more excuses to take 6 months over reviewing our 7000-word pieces of genius research.

It’s also the right weather for the sempiternally worshipped Duchess of Cambridge (DoC) to properly dazzle the world with her impeccable figure and flawless sense of style, so I thought I’d corner her for an interview about how we can transfer her otherworldly sartorial perfection to our academic writing.

CB. Hello, Your Cantabrigian Highness! How was Australia?

DoC. It was ever so interesting. Among other things, I discovered that giraffes have even longer tongues than the men who watched the slow oscillation of my sister’s derriere at my wedding.

CB. Right… Tell us, pray, o eternal empress of chic – what tips from your wardrobe and attitude can we apply to academic essay- and article-writing?

DoC. Well, to begin with, we must all agree that the ideal outfit is perfectly fitted, but of a lovely bright or pastel colour.

CB. Indeed, you are not a fan of baggy tops and maxiskirts in fifty shades of browns and greys. What’s the tip here?

DoC. My dear, the ideal article is carefully trimmed to fit exactly the subject matter – no fluffy extras, no bits of fabric hanging out here and there, and rigorously no asymmetry. Be scissor-happy: as close to the body of the essay as you can be. No blurry tulle or misty gauze: use honest, clear, tangible fabrics. But to counteract this rather severe tailoring, allow yourself a generally bold, bright, youthful, sharp tone of voice. White and black are to be kept for important occasions: black for paradigm-shifting articles, and pretty, lacy white lies for academic reviews of your friends or colleagues’ latest books.

CB. All of this should be monochromatic ?

DoC. Well, I do like monochrome, but accessories will help you ensure it doesn’t end up being monochord. Allow yourself little deviations from the overall tone – but only where it matters. A nice little controversial quotation to top your introduction like a curly fascinator, an interesting clutch to set off a dull paragraph towards the middle of the essay.

CB. And a grand, lyrical, flashy conclusion?

DoC. My goodness, no! It would attract attention solely onto itself, to the detriment of the body of work. Conclusions should be like my shoes: very bland, distanced enough from the ground that they’re not flat, but certainly no platforms. Let the essay speak for itself and end sensibly.

CB. That’s helpful, Your Highness, but some people would accuse you of taking too few risks. Aren’t we going to end up with a rather classical style?

DoC. This is where another rule comes into play: hair should be down unless absolutely necessary. This will add unexpectedness, a sense of welcome playfulness, a certain je ne sais quoi of unpredictability. Structure and plan everything, but always leave something unprepared – something for the winds of inspiration to frolic around with.

CB. Erm what? Your hair is unprepared?

DoC. *coughs* Well, it’s prepared in a special way that makes it feel natural and unexpected when the breeze plays around with it. Think of it as your scholarly background – all that knowledge that you’ve accumulated over the years. Some of it is already present in your structure – you’re consciously integrated those sources, you know you’ll mention them at some stage. But the rest is still there, maintained, curled and trimmed by years of taking notes, rereading them, forgetting them. Not exactly unprepared, but let’s say, artistically free-floating. A flick of the wind and ta-dah! who knows which idea might come and kiss your cheek when you think you’ve got your whole argument sorted?

CB. What is it with knees? Why do you rarely show your knees?

DoC. Knees are like transitions between subparts. They do all the hard work, but they are aesthetically displeasing and lack grace. Try to conceal them whenever possible. That said, should an impolite gust of wind ruffle your skirt as you get down from an airplane, the effect can be quite alluring; use this tip sparsely, to showcase, for a brief moment, the strength of those solid hinges of yours.

CB. What can you tell us about handling our ideas?

DoC. Take inspiration from the way in which I artfully handle little Prince George to show him around to my people: from all different angles, and apparently effortlessly. It looks like a nine-month-old healthy baby isn’t at all too heavy for my impossibly delicate arms. Cultivate that style. Show all the facets of your ideas, trying to make it sound like it’s very easy to hold them for a long time in improbable positions.

CB. Is it always necessary to remind everyone of your status by constantly flashing your tacky diamond and sapphire engagement ring?

DoC. Yes, dear. It’s called a self-citation. You’ll see when you’ve got actual work to show for your importance in the field: you’ll refer to it absolutely all the time. You’ll find, in fact, that I’m being quite restrained, only alluding to my status in one place per outfit. Of course, you can’t do that yet, because you’re a nobody who hasn’t yet done anything worthy of unsubtle allusions.

‘I refer you to my previous work in the field’

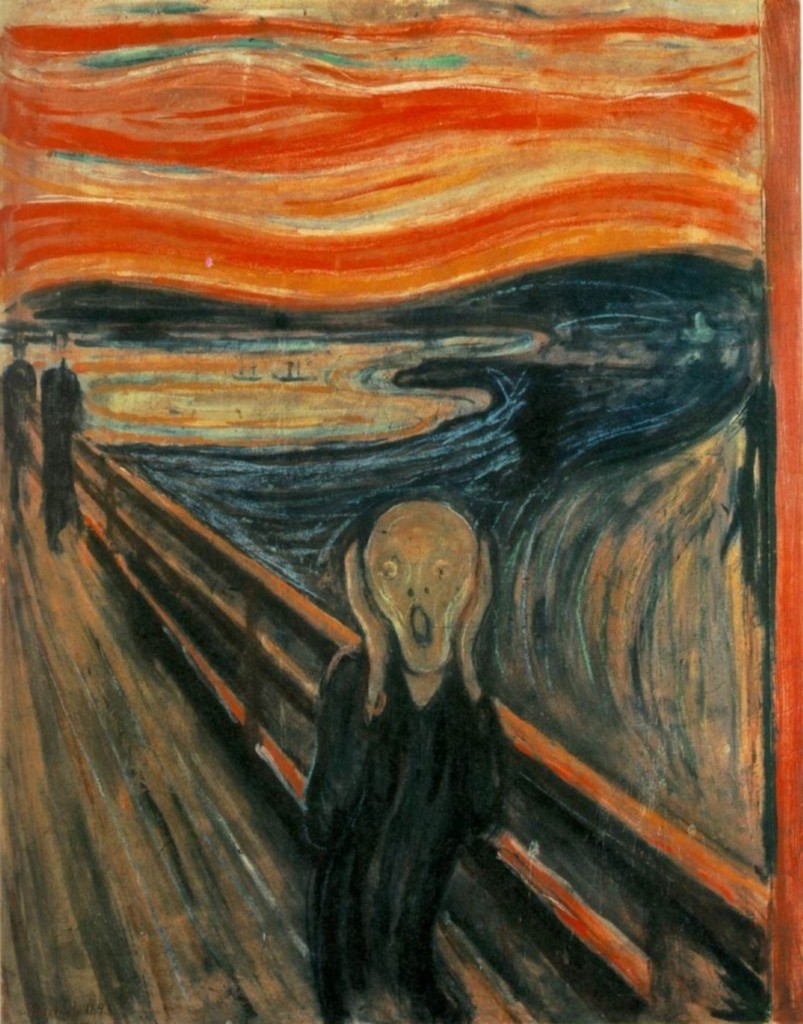

CB. Thanks for that. A final question, Your Royal Youness. People like me have days when they have pimples, or scruffy hair, or really no wish to squeeze our feet into high heels. For some of us, it’s every single day. What can we do if we really can’t follow your example, o grand guru of demure fashion?

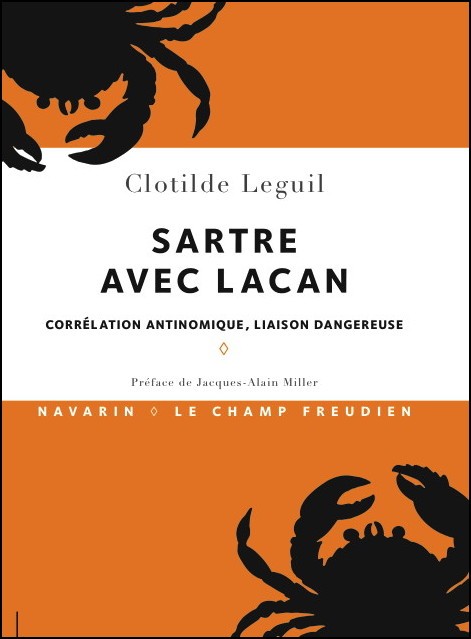

DoC. I’m not interested in such people. I’m sure they can find their own style guide to follow. Go ask Lady Gaga, I heard she coached Slavoj Zizek.

Thank you, tabloidal deity, for granting us half an hour of your busy schedule. She has now returned to the hyperactive nothingness of her royal duties, leaving us with some hope that we shall one day find true love, in the form of a permanent and salaried position, within some academic establishment. And perhaps we will soon parade, in front of a crowd of excited journalists politely complimentary colleagues, a cuboid baby freshly delivered by an academic press.