(… and I somehow managed to forget its date of birth, which is a bit careless and doesn’t bode well for the future if I ever have kids…)

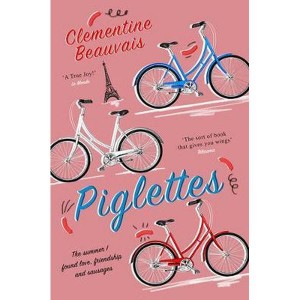

So, erm, while I was in Spain for some work-and-holiday time, Piglettes, written by me and translated by me but published by the great people at Pushkin Press (thank you Daniel and Mollie in particular!), came out into the world!

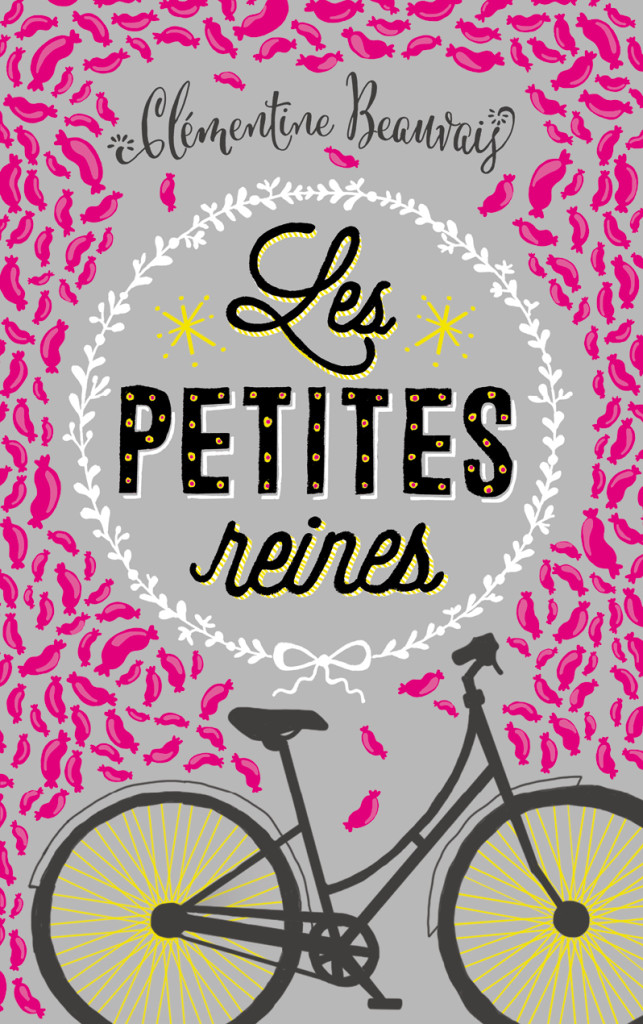

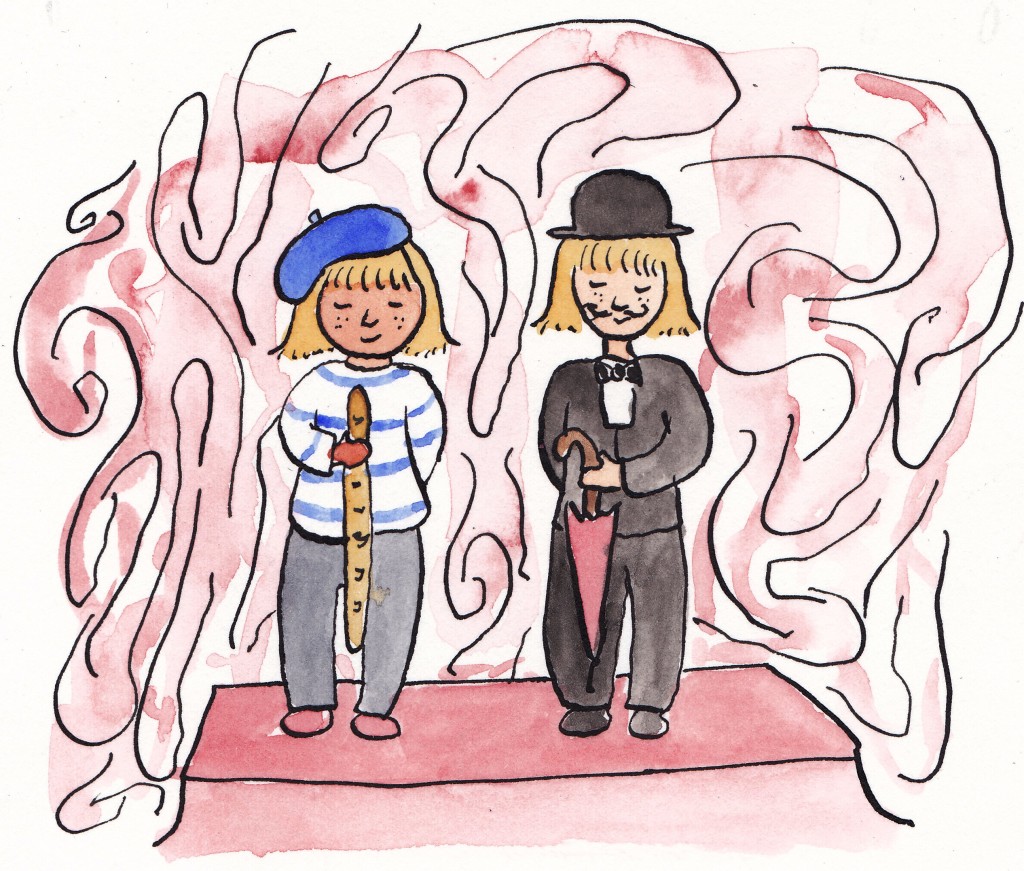

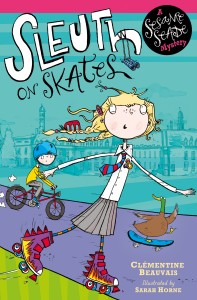

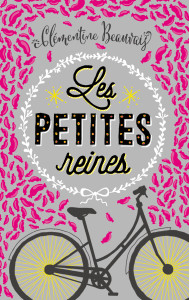

And here it is!

It’s lovely and pink (but not too pink) and LIGHT, which means you can tuck it into your cycling shorts to take it around on a bike ride. Sorry, what? Why would you do that? Well, because that’s what it’s about. Cycling. And sausages. And ugliness competitions… also about gate-crashing the July 14th Presidential garden party at the palace of the Elysée in Paris.

It all makes sense, somehow, in the book. I think… Here’s the official summary:

Awarded the Gold, Silver and Bronze trotters after a vote by their classmates on Facebook, Mireille, Astrid and Hakima are officially the three ugliest girls in their school, but does that mean they’re going to sit around crying about it?

Well… yes, a bit, but not for long! Climbing aboard their bikes, the trio set off on a summer roadtrip to Paris, their goal: a garden party with the French president. As news of their trip spreads they become stars of social media and television. With the eyes of the nation upon them the girls find fame, friendship and happiness, and still have time to consume an enormous amount of food along the way.

Piglettes is strange for me because it’s new news and old news at the same time. It came out in French as Les petites reines in 2015.

bikes, black pudding, rural France, and friendship.

By then, I’d published a few books already, which had had modest echo (very very modest).

And then Les petites reines came out and within a year, my life (at least, the side of my life that’s French and writerly) had changed quite a bit. This is the part where I say that it was a bestseller in France and sold rights to the stage, the cinema and many translations, and also won tons of awards, including some of the most major national ones, and was on the IBBY International Honour list the next year. I also starting getting many more invitations to come speak to schools and in book fairs. It was the beginning for me of a much stronger involvement with the French children’s literature community, its debates, its questions, its politics, and its people.

And more importantly perhaps, I started receiving many, many emails from young readers, and from their parents (and even grandparents) sometimes. And I still do, often. And I know it’s being borrowed hugely from school libraries, which makes me very happy.

Right, I have now said those things which are kind of required of anyone self-promoting I think. Ah no, wait, there’s more. There are already some really nice early reviews of the book in English – thank you SO much to the bloggers and journalists who have already read it – in France, word-of-mouth was absolutely crucial to the success of the book and I’m indebted for absolutely ever to the bloggers and vloggers who pushed it so much from the beginning. So here are some early comments here:

- Did you ever stop to think and forget to start again?: There is a special place in my heart for young adult books that dance with joy over sausage recipes. What an utter treat this book is. I want to wrap my arms around it and never let it go.

- Blogger’s Bookshelf: This is an uplifting story, guaranteed to make you giggle. Beauvais handles the issues in this book with a light hand and an excellent sense of humour and I would definitely recommend it to all teenage girls and anyone else who wants a truly fun and funny read about friendship, growing up, and selling sausages in the French countryside.

- The cosy reader: I absolutely adored this book. It was fun and sweet and heart warming, but it also tackled some pretty big issues-cyber bullying, disability and war to name a few, in its stride, dealing with them in a sensitive and refreshing way.

- The book bag: I found this a rich and intelligent read, able to get away from the straightforward diary-of-the-journey format, willing to surprise us, and at least able to make us all (even me) fall in love with Mireille.

- YS Book Reviews: This beautiful and funny book explores the troubles and triumphs of being a teen through the eyes of a witty, philosophical, and slightly awkward teen. … Mireille’s voice and character are wonderfully authentic with unflappable confidence and inelegant missteps mixed together for a potent storyteller on a journey of self-discovery.

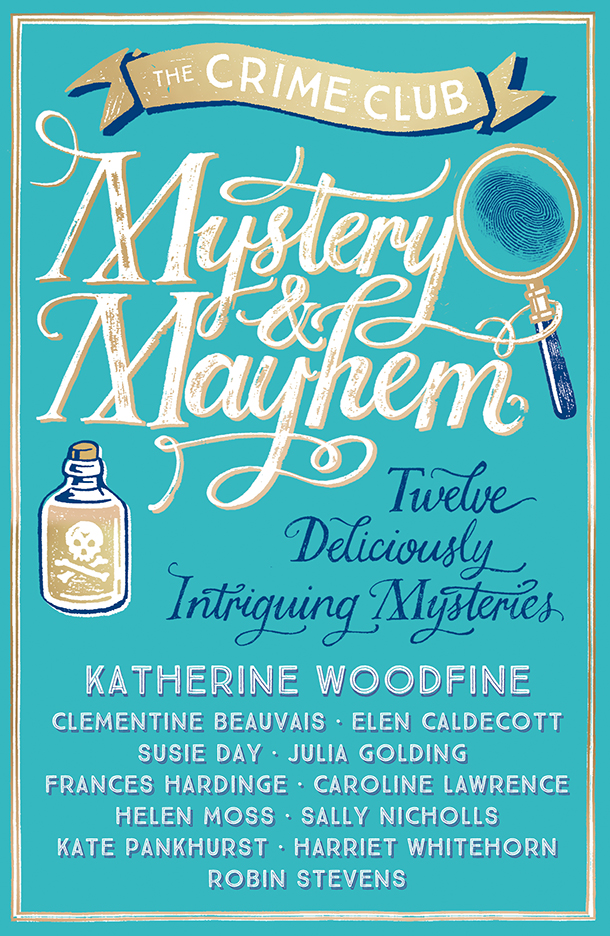

- On The Copper Boom‘s Summer Reading List! Alongside my friend Robin Stevens’ amazing Murder Most Unladylike, which I can only approve of…

I hope you like the book as much as the French readers seem to have done. I hope it’s a bit different to things you might have read before.

And more importantly I really hope it makes you laugh, because it was the whole point of the endeavour to begin with.

Happy reading!