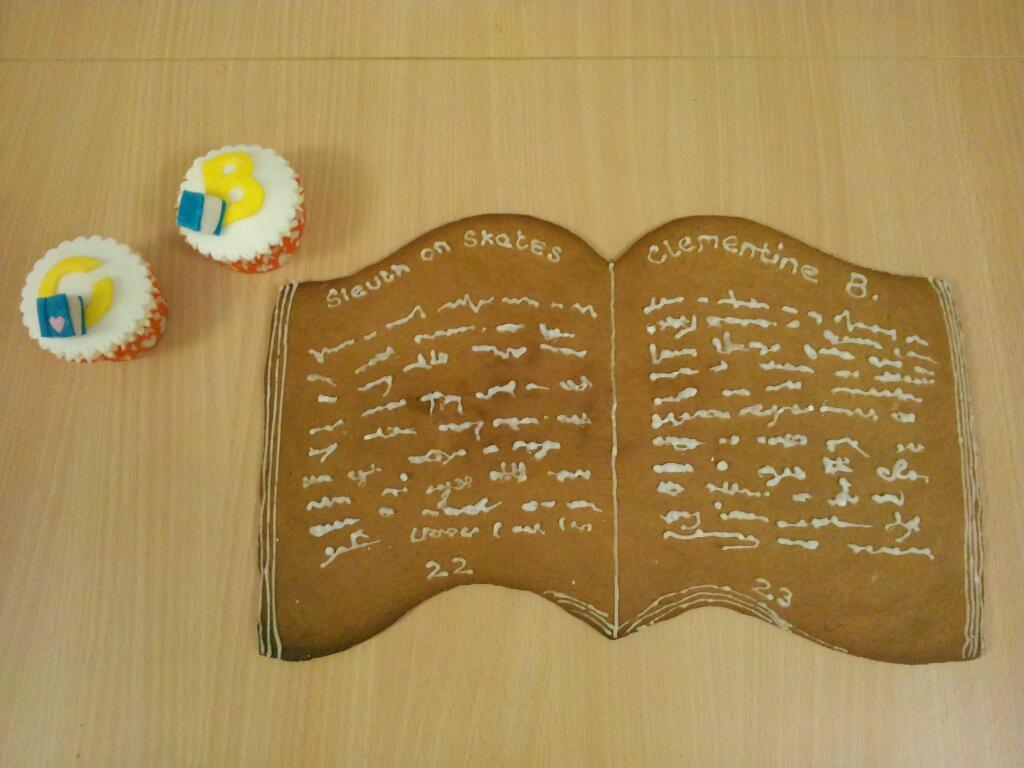

School visits in primary school are nothing like school visits in high school. Primary school is Care Bear land: children are enthusiastic, chatty, unhibited, fun, on the edge of their seats. You leave feeling exhausted and deliriously happy, with tripled self-esteem. Especially when they’ve made you a book-shaped cake and cupcakes with your initials.

Yeah I’m showing off.

High school is resolutely different. Something happens in the first few weeks of Year Seven – you can spot it as soon as you come through the door. Pupils look distrustful, sarcastic – they stare at you, and then at one another, exchanging funny little smiles. Some of their questions and comments are unsettling, if not downright offensive. Evidently on purpose. All the more so if you’re young, female and blonde.

But after a few minutes, if you show them that you’re on their side, you gain their trust and the atmosphere gets more relaxes. And then you can talk about really interesting things, and have fun, and tackle serious topics, and let them speak about themselves, and listen to them.

So it’s not the same dynamic at all in a primary school visit and a secondary school visit. In particular, though I often conclude my primary school visits with a reading, it had never come to my mind to do a reading for high school students.

Well, I was having lunch last year during a literary festival in France and talking to another author who suggested I should. He said teenagers loved being read to. I didn’t believe him for a second; I put on my best polite face (“Really? How interesting!”) while secretly thinking “The poor man is completely disconnected from the real world – the teenagers he read his books to must feel terribly offended to be treated like babies.”

Not a teenager.

Coincidentally, though, that very same afternoon I did a school visit in a Year Nine class where the teacher said to me in front of everyone: “The students would very much like you to read an extract from your book to them”. They’d already all read that book (La pouilleuse), or were supposed to (in France, you do school visits only when schools have studied your books).

Since a teacher had asked, I wasn’t going to say no – like most academics, I’ve always scrupulously followed teachers’ orders – but I thought, once again, that the poor adult was completely deluded: teenagers, I firmly believed, don’t like being read to.

Of course I was completely wrong. Hardly had I begun to read that I noticed the extraordinary quality of the silence that had fallen on the room. The students were staring into emptiness, or at their hands or feet. They didn’t look enraptured, hypnotised or stunned – simply silent, and listening.

What struck me was how different that silence was from the silence you get when you read something to primary school children. Primary school children fidget, giggle, whisper. They’re so used to being read to, it’s just normal to them.

Not to those teenagers. They’d lost the habit – the habit of finding themselves in a situation where there’s nothing else to do than to listen to a word after another, to each sentence with its rhythm and musicality. For them, I could tell, it felt new.

(And no, I’m not subtly bragging about the rhythm and musicality of my book; I’m pretty sure I could have read them anything. It was all about the situation, not the text.)

(And no, I don’t have his voice.)

When I finally found a place to stop, there were a few more seconds of that silence. Then they started moving again, and some of them said, “Just a few more pages…”

Since then, I always try to take time at the end of my high school visits to read extracts from the book. Something always happens. I know, now, that literature teachers know it – and sometimes take advantage of this amazing quality of their listening, to read them texts that they wouldn’t read themselves with the same focus, the same attention.

At the risk, of course, of gradually breaking the spell…

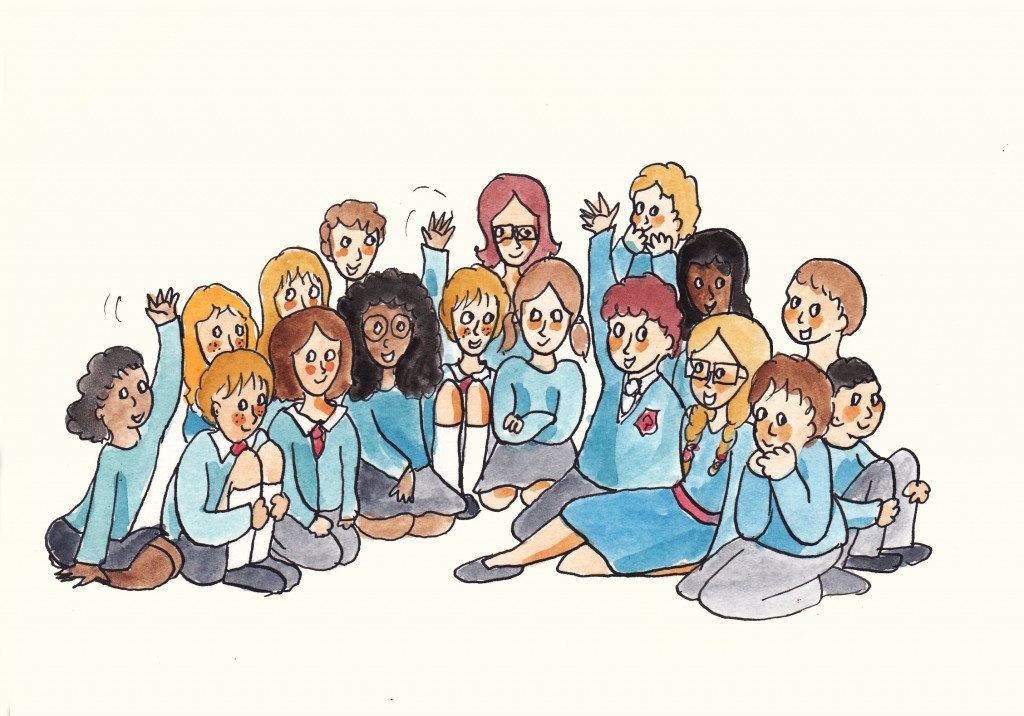

It’s the week around World Book Day in the UK – and authors are visiting schools everywhere to meet enthusiastic children who want to READ!

It’s the week around World Book Day in the UK – and authors are visiting schools everywhere to meet enthusiastic children who want to READ! Julian Sedgwick does knife-juggling:

Julian Sedgwick does knife-juggling: But even the rest of us, who just talk, ask questions and show pictures, make children happy:

But even the rest of us, who just talk, ask questions and show pictures, make children happy: So this is just a little post to say THANK YOU to schools, bookshops and parents for organising all this –

So this is just a little post to say THANK YOU to schools, bookshops and parents for organising all this –