Dear UK/US readers, you might have heard of the Hollande/Gayet affair, but that’s so yesterday now. Something much more scandalous has taken its place in the French media: a children’s book.

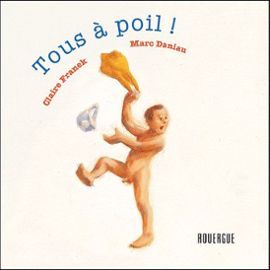

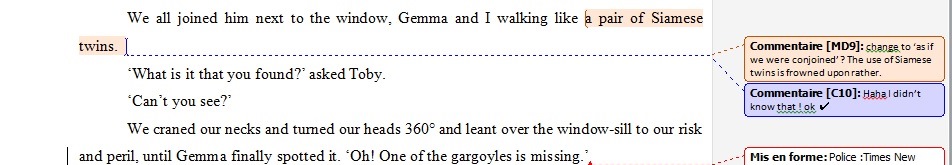

On Sunday, Jean-François Copé, head of the socially-conservative, neo-liberal party (Sarkozy’s party, right of centre) discovered children’s literature. It was a bit of a shock: the poor man’s blood ‘curdled’ (his own terms) when he laid eyes on this picturebook:

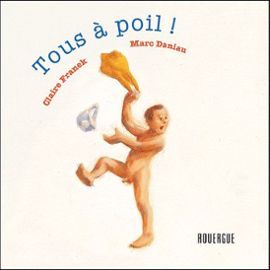

Tous à poil (“All naked”), by Claire Franek and Marc Daniau, had since 2011 lived a quiet, fairly unnoticed life on libraries’ bookshelves. Its only claim to fame was that it had been, like 499 other books (including one of mine), included in the list of ‘recommended reading’ for schools by the Ministry of Education.

Tous à poil (“All naked”), by Claire Franek and Marc Daniau, had since 2011 lived a quiet, fairly unnoticed life on libraries’ bookshelves. Its only claim to fame was that it had been, like 499 other books (including one of mine), included in the list of ‘recommended reading’ for schools by the Ministry of Education.

This fun little picturebook shows dozens of people stripping: Dad, Mum, children, the neighbours, the schoolteacher, the President – and going to the beach. The avowed aim of the author, not that it matters much, was to trigger smiles in the child reader and de-dramatise body image.

Jean-François Copé, however, was not amused. He brandished the odious picturebook during an interview on TV and proceeded to read it out loud, making sarcastic comments and noting that ‘at some point, in France, we’re going to have to stop to think about what we’re doing to our children.’

Jean-François Copé overestimating the size of his own brain

By Monday morning everyone on French news was talking about this book, and about children’s literature in general, and children’s editors and authors were being interviewed. It had been a while since children’s literature had been on the news so much, and it was actually funny, so we all thanked Copé for the sudden rise in interest for our work.

By Monday afternoon we’d all stopped laughing. Because no sooner had Copé finished his diatribe that a quagmire of Catholic, right-wing extremist ‘associations’ and groups declared war on politically committed children’s literature, stating that their next plan was to ban from school libraries offensive books such as Tous à poil.

Their target, in fact, is perhaps more accurately all those books that promote gender equality, or hint at the fluidity of gender performativity. And of course, books that feature same-sex relationships. For the first time in France, which is by no means a prudish country for children’s literature, we see emerging a very strong desire to prevent librarians, teachers and booksellers from stocking and recommending children’s books that present ‘alternative’, radical, or even slightly transgressive ways of life.

And it wasn’t the first time – things like that have been happening increasingly often for the past couple of years.

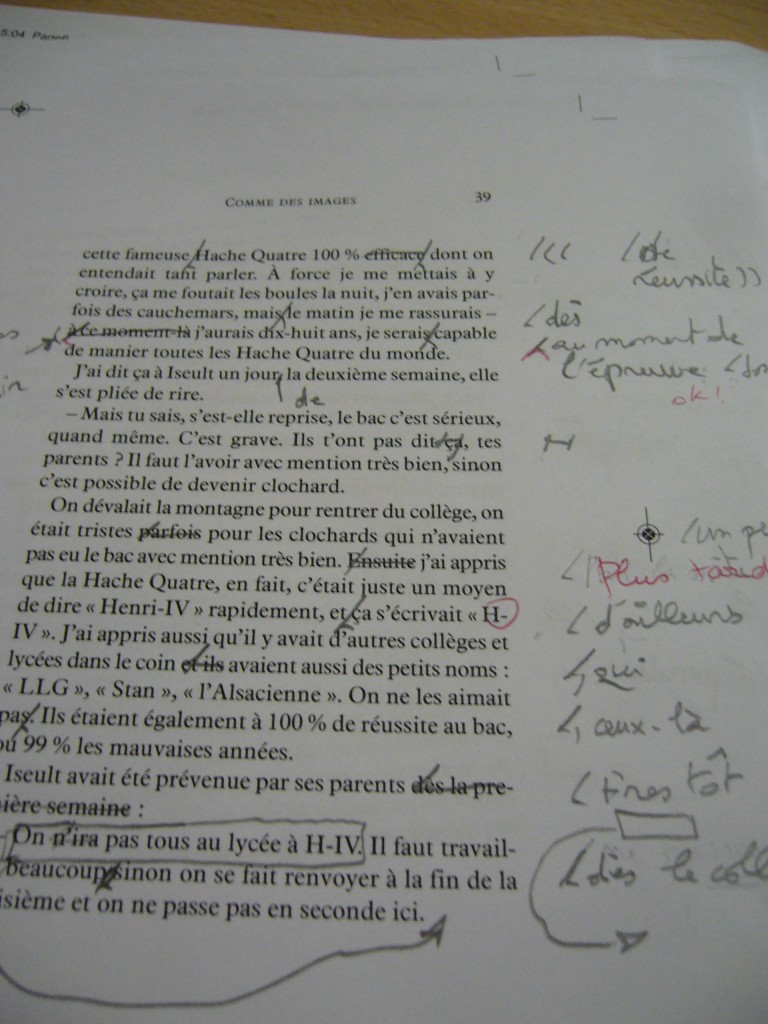

Last week, there’d been a much smaller, but (to us children’s literature people) just as noticeable furore on the Internet about a children’s novel called Je porte la culotte/ La journée du slip. Recently published (also by Le Rouergue), that novel contains two stories; one in which a little boy wakes up as a girl, and the other one in which a little girl wakes up as a boy.

A children’s literature blog reviewed it, and the review caught the eye of extremist groups. The authors received death threats. Reading the comments on the original blog post is enough to make you want to stop writing politically committed children’s books forever.

You might be wondering where all that is coming from – France, after all, has a long tradition of subversive and politically radical children’s literature. Yes, but conservative politicians and traditionalist Catholic activists are only just beginning to discover them. Or at least, they’re only just beginning to make their opinions heard about them, because the media are now listening to these small clusters of people who are becoming more and more organised.

It had been brewing for a while but truly took shape last year, when François Hollande’s law legalising same-sex marriage, which we supposed would be just a formality, woke up a normally silent and disorganised fringe. Astonished, we watched people demonstrate, sometimes violently, against that most banal of requests – allowing same-sex couples to marry.

The movement didn’t stop with the gay marriage laws being passed. More recently, galvanised by Spain’s proposed restrictions on abortion, the same activist groups took to the streets again to protest against abortion in France.

Now they’ve found yet another thing to protest against. The Minister of Education as well as the Minister for Women’s Rights in the Hollande government are currently encouraging schools to teach children about the non-essentialism of gender (you know, that idea that was more or less radical in the fifties). Children are asked in schools to engage with the stupendously controversial idea that not all nurses need to be female nor all air pilots male.

Activists are calling this the rise of ‘gender theory in schools’, which refers to absolutely nothing else than the strawman they created by naming it so. Spectacularly, two weeks ago, one of their ‘leaders’ sent hundreds of texts to parents of young children, urging them not to put the little ones at school that day: they were going to be ‘taught to masturbate’, there would be ‘a sexologist coming to school’, and, wait for it, ‘Jewish doctors would come and examine their willies, telling them that they can change them for vaginas if they don’t like them.’

I know.

Jean-François Copé’s absurd attack on Tous à poil thus takes place at a hugely heated time in France, and here we go, he’s given those people another thing to focus on: they’ve already declared that their next battle will be children’s literature.

What power do these people truly have? It’s difficult to say. They’ve dominated our news for over a year. They’ve resorted to acts of violence. And this is all happening some twelve years after the extremist right wing party, Jean-Marie and Marine Le Pen’s Front National, reached the second round of the national elections for the French Presidency.

So we children’s writers and illustrators might be posting funny pictures of naked children in children’s books on our Facebook profiles, and Photoshopped pictures of naked Jean-François Copé, and showing support for our colleagues who inadvertently launched a media storm, but we’re not as merry as we may look. It’s ridiculous, yes, but a dangerous kind of ridiculous.

We’d really prefer children’s literature to make headlines for a different reason. In the meantime, we’ll retreat back to our quiet little Internet niche of friendly forums, blogs and Facebook pages. And write yet more politically committed books, because clearly they’re increasingly needed.

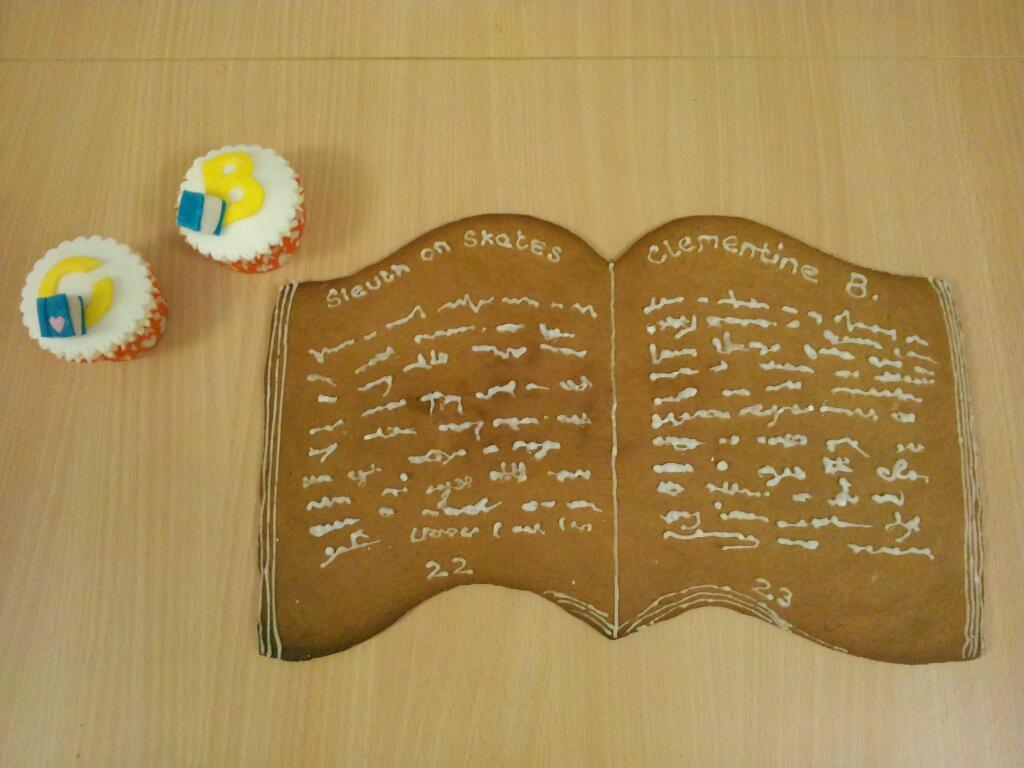

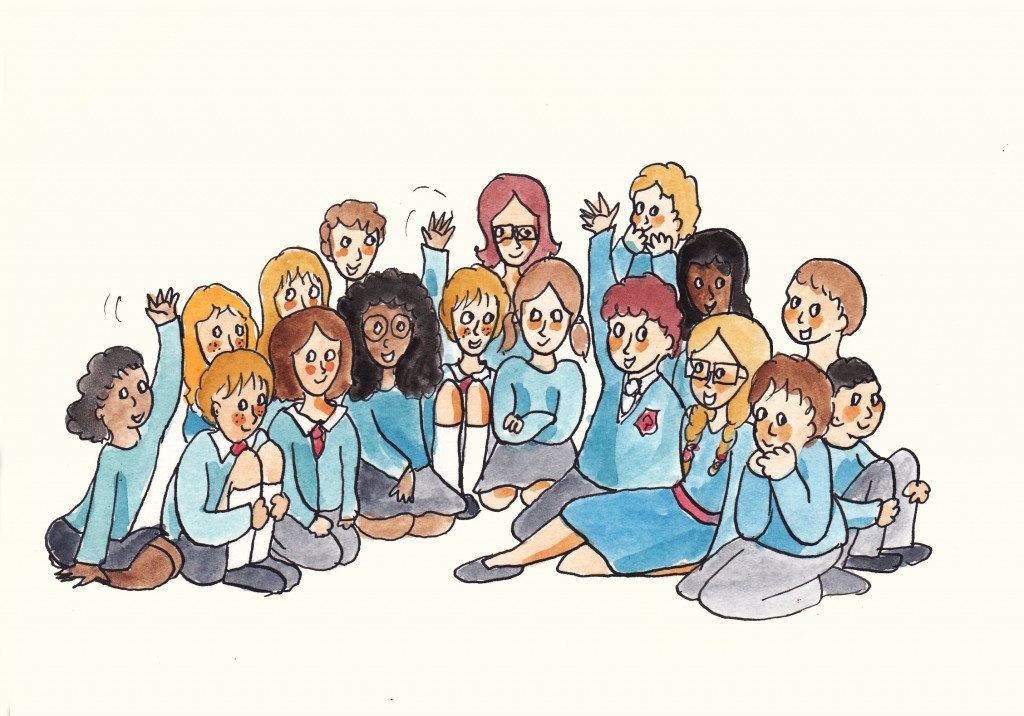

It’s the week around World Book Day in the UK – and authors are visiting schools everywhere to meet enthusiastic children who want to READ!

It’s the week around World Book Day in the UK – and authors are visiting schools everywhere to meet enthusiastic children who want to READ! Julian Sedgwick does knife-juggling:

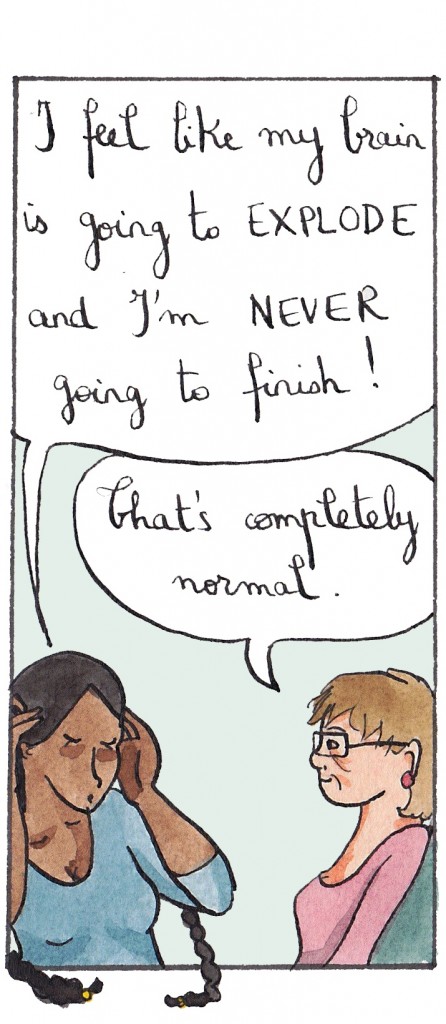

Julian Sedgwick does knife-juggling: But even the rest of us, who just talk, ask questions and show pictures, make children happy:

But even the rest of us, who just talk, ask questions and show pictures, make children happy: So this is just a little post to say THANK YOU to schools, bookshops and parents for organising all this –

So this is just a little post to say THANK YOU to schools, bookshops and parents for organising all this –