I briefly mentioned the accursed phenomenon in this post. That phenomenon, well-known both to children’s writers and to academics in children’s literature or education, is the dreaded, dreary, dreadful deadlock of the argument from parenthood.

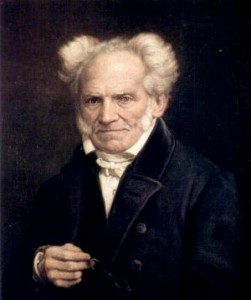

An argument strangely overlooked by Schopenhauer in his Art of Being Always Right.

An argument strangely overlooked by Schopenhauer in his Art of Being Always Right.

This argument goes like this:

A: What I mean is that Book X can be criticised for its sexism.

B: Well, my little Phlox loves it!

A: I’m not saying children don’t like it, I’m saying it’s ideologically problematic.

B: Well, she isn’t bothered by the ideology!

A: It is quite possible that she might not notice it.

B: Children notice everything. They have the third eye. They are magical clairvoyants of miracle.

A: I’m not su-

B: Do you have children?

A: No.

B: If you did then you’d know. At the moment you don’t so you don’t.

A: Oh, ok then.

B: You know, I used to be like you, believing all the myths. For example, the idea that we can bring up girls not be girly and to be equal to boys. But then I had Phlox, and I gradually realised I was wrong. I observe her closely. She is naturally attracted to pink, and even at two years old she was enthusiastically helping me clean the house.

A: Ah, I guess essentialism is right then.

B: I used to believe that there was no maternal instinct, but then I held little Phlox against my chest and took my breast out of my bra and pressed the nipple against…

A: Can we not talk about this.

B: I love my children.

A: Oh I know.

B: Do you hate children?

A: No, I…

B: You must do, if you spend all your free time nastily disparaging all the books they like.

A: I don’t have anything against children.

B: THEN WHERE ARE YOUR CHILDREN?

(etc.)

I am barely exaggerating, and please don’t go and think that those things don’t happen at the most inappropriate moments, e.g. in the Q&A session at the end of a conference paper. It happens at least once in every conference, but often more. The following is a real (honest, unedited) argument from parenthood we heard at a conference last year.

The paper was a Marxist critique of the commercial myth of Santa Claus. Right after the talk, a hand shot up into the air. At the other end of the arm, a middle-aged lady. Her question, verbatim:

‘Do you have children?’

The youngish lady who’d given the paper looked for a minute like we’d have to push her eyeballs back into her head in a very short while. Eventually she stammered: ‘Well, I … Actually, I don’t think I should be answering this question…’

Not in the least disturbed, her questioner said, ‘Ok. Because I have to say, you talk about all these things, but I have children, and you don’t take into consideration the sheer magic of Christmas, the beautiful moment that it is for them, you can see it in their eyes…’

Bis repetita. I’m not quite sure what makes those people so OK, in the midst of an academic discourse, with bringing to the debate their own personal experiences of having created another human being from scratch. And more staggeringly, with asking straight out if their addressee has achieved the same ‘feat’ (presumably they would then be on the same wavelength).

What if the presenter couldn’t have children? What if she’d lost a child? This isn’t exactly the kind of revelation you want to hear in a busy panel sessions.

What if she didn’t ever want children? Would that make her Marxist reading of Christmas less valid?

Even when people don’t directly ask if the person has children, the argument from parenthood must be, I’m sure, extremely offensive and painful to academics who for some reason that they don’t need to disclose cannot or do not want to have children, and/or have had traumatic experiences in this very personal side of their lives. They must feel like they should be able to carry on with their academic work on childhood without it being hammered into their heads that it is incomplete without the insights of actual parenthood, whether or not from choice.

You don’t hear haemorrhoid specialists being asked by other haemorrhoid specialists in the Q&A session, ‘Excuse me, but have you got haemorrhoids yourself?’ You don’t see fruit fly specialists lyrically raving on about the cuteness of their three-legged, twelve-winged, forty-eight-eyed wonders in the middle of an academic conference. OK, maybe you do. But why is it that children’s literature criticism – and education in general, I think – which makes people think it’s an OK thing to do?

It is NOT an OK thing to do, for the following reasons and many more:

- Arguments from parenthood, in general, are extremely conservative. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard parents implicitly justify patriarchy, ‘fear of the racial other’, etc, and their own life choices as academics, thanks to their kids. Simply from observing that their boys tend to prefer gun toys (‘even if I offer him dolls, he’ll choose guns!’), that their babies are more scared of the black neighbour than the white postman, they happily spring back into obscure essentialism.

- Arguments from parenthood are a form of religious speech, in the sense that there is no possibility for anyone to refute them. If you’re not a Parent, you can’t know because you’re not a Parent. (“argument from belonging to a completely different sphere of experience”). If you’re a parent, you can’t know either, because you don’t realise that my kids are more right than yours. All I can say is that I respectfully tolerate your faith, but I personally belong to cult of the Non-Childed, or to the cult of the Childed-With-Other-Children-Than-Yours, and therefore according to your rules I can’t know.

- Arguments from parenthood come from the absolute and intimate and clearly wrong conviction that one’s children can’t possibly be biased, influenced, deficient in some way or ignorant. If Phlox, Amaryllis and Cyprian are acting this way, it’s because it’s in the Great Nature of Childhood to be so. They are eternal vessels of truth. My obsessive-compulsive observation of their every move is therefore putting me in touch with Pure Childness. And it is beautiful, oh is it beautiful. (This brutally changes, by the way, at adolescence – I have much more patience for parents bemoaning the constant annoyance to their lives that is their teenager, since it at least promises some anecdotal entertainment.)

- No one likes arguments from parenthood, even those people who engage most often in them. In fact, those people are probably the biggest haters of arguments from parenthood – when used by others. You can tell from their scrunched-up faces that they are exceedingly annoyed when another person has the cheek to argue from parenthood before them. They want to yell out, ‘That’s my argument!’. They want to interrupt the impertinent speaker and give their version (the true one) of Pure Childness.

Sometimes a verbal ping-pong game will engage whereby two people will issue arguments from parenthood in the attempt to prove, superficially, an academic point, but in reality, one’s superior parenting skills and superior children.

Variations on the argument from parenthood include the argument from grandparenthood, the argument from aunt- or unclehood, the argument from godparenthood, the argument from teachinghood (which I would consider slightly more acceptable), and the cutest of all, the argument from siblinghood, which is the property of young PhD students who think with anguish that there must be some truth to this type of argument and they should do their best to get into the clique. I’ve been there.

Questions containing arguments from parenthood are not questions, they are family stories. Answers containing arguments from parenthood are not answers, they are family stories. Arguments from parenthood are not arguments, they are family stories.

I’m more than happy to listen to family stories over coffee and cake. But when giving or listening to a conference paper, I want to be free to analyse your daughter’s favourite book and say that it reinforces male domination and racial discrimination without it being perceived as a personal attack on her aesthetic taste. I want to be free to say that the fascination we have for childhood stems from existential concerns incommensurate with the objective value of the human beings that represent it without being told that I’ll understand when I squeeze the glutinous fruit of my own entrails in my arms for the first time.

And I really, really don’t want to hear about episiotomies.

Especially after I finally caved in and Googled the thing and realised it means this.

WHAT.